The Cold War, a period defined by ideological tension between the United States and the Soviet Union, was more than just a struggle between two superpowers. It was a global contest that swept up countries from all corners of the world, including Africa—a continent that was, at the time, largely under colonial rule or just emerging into independence. Amidst this backdrop, China, a rising communist power, sought to establish itself as a key player in Africa’s evolving political landscape.

For much of the Cold War, Africa was a stage where rival powers competed not only for political influence but for access to vital resources, strategic positioning, and ideological dominance. What made China’s approach to Africa unique was its non-colonial, anti-imperialist rhetoric, which resonated with newly independent African nations, many of which were grappling with the legacy of colonialism. But the road from ideological solidarity to diplomatic engagement was neither smooth nor straightforward.

China’s Early Involvement in Africa

In the early 1950s, as the Cold War intensified, China was still finding its footing on the global stage. The Communist Party had consolidated power following the 1949 revolution, and the government was determined to assert itself as a leader of the Global South. In Africa, the anti-colonial movements were gaining momentum, and China saw an opportunity to position itself as a champion of the continent’s struggle for independence. China’s approach was also shaped by the belief that African liberation movements aligned with its own quest to dismantle imperialism and colonialism.

At first, Beijing’s diplomacy was largely a byproduct of its ideological alignment with Africa’s emerging nationalist leaders. China extended moral and material support to countries and movements fighting for independence, including the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa, the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN), and various liberation movements in countries like Angola and Zimbabwe. This support was not just ideological but also financial, with China providing scholarships for African students to study in Beijing, as well as funding for infrastructure projects in newly independent nations.

The Cold War Divide: China vs. the Soviet Union

As the Cold War progressed, however, the geopolitical dynamics began to shift. The Soviet Union, which had been China’s ally in the early stages of the revolution, began to drift from Beijing after the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s. The ideological rift between the two communist powers opened up opportunities for China to differentiate itself in its dealings with Africa. While the Soviet Union primarily focused on supporting Marxist-Leninist regimes and fostering close ties with governments like those in Egypt and Ethiopia, China took a more diversified approach, focusing on grassroots solidarity and direct partnerships with a broader spectrum of African leaders, including those not aligned with communism.

In some ways, the Cold War turned Africa into a chessboard of competing ideologies, with the Soviet Union backing socialist regimes and the West championing capitalist democracies. But China’s position was different—it was not trying to impose a singular ideology on African nations. Instead, Beijing’s message was one of self-reliance, anti-imperialism, and support for national sovereignty. This resonated with African leaders, especially as they navigated the complexities of post-colonial nation-building and were wary of neocolonial influence from both the West and the Soviet bloc.

China’s engagement with Africa was pragmatic as well. Beijing’s focus was not just ideological but also rooted in realpolitik. Many African nations, particularly those in East and Southern Africa, had key natural resources that were of great interest to China’s rapidly growing economy. For instance, in the 1970s, China made significant investments in the construction of the Tanzania-Zambia Railway (Tanzam), a major infrastructure project that linked Tanzania’s port of Dar es Salaam with Zambia’s copper mines. This was not just an act of altruism—it was a strategic move that gave China access to important mineral resources while simultaneously strengthening its influence in the region.

The Economic and Diplomatic Shifts

By the late 1970s, as China emerged from the Cultural Revolution under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership, its foreign policy underwent a significant transformation. China moved away from a strict ideological stance and towards a more pragmatic, economic-driven approach. The opening up of China’s economy and its pursuit of economic development meant that Africa’s natural resources—especially oil, minerals, and other raw materials—became even more attractive to Chinese policymakers. With Africa’s vast untapped potential, the continent became an essential partner in China’s pursuit of economic growth.

In the context of the Cold War, Africa’s importance was heightened by the rise of proxy wars across the continent. Countries like Angola, Mozambique, and Ethiopia were caught in conflicts fueled by the ideological competition between the U.S., the USSR, and China. While the U.S. and the Soviet Union sought to align with rival factions in these conflicts, China often found itself supporting liberation movements that were not aligned with either superpower, further cementing its role as an alternative to both Western and Soviet dominance in the region.

Legacy and Long-term Impact

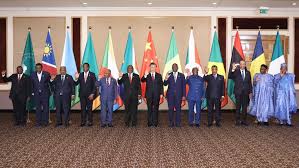

By the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s, China had solidified its position as a key player in Africa. Beijing’s combination of political support, economic investment, and ideological solidarity with African nations had made China a trusted partner for many of Africa’s new governments. The 1990s marked the beginning of what would become a new era in China-Africa relations—one driven not by Cold War geopolitics but by economic interests, trade partnerships, and long-term investments.

Today, the relationship between China and Africa is often defined by China’s role as a leading trade partner, investor, and builder of infrastructure across the continent. Yet the foundation of this modern partnership was laid during the Cold War, when China’s non-colonial stance, support for independence, and practical engagement with African nations helped to reshape the geopolitical landscape. The Cold War may have ended decades ago, but its legacy in Africa-China relations is still felt in the modern political and economic ties that bind the two regions together.

As African nations continue to rise on the global stage, the historical context of their relationship with China during the Cold War remains a crucial chapter in understanding the evolution of global geopolitics and the shifting alignments of today’s international order.